Lawrence University is mourning the loss of Joseph F. Patterson Jr. ’69, a former university trustee, successful New York real estate entrepreneur, and one of the greatest players in Lawrence football history. He died Aug. 17 at age 74.

Patterson’s legacy at Lawrence runs deep—football exploits that teammates and fans still talk about 50 years later; leadership among Black students that led to the establishment of Lawrence’s first diversity center in the late 1960s; unrelenting advocacy for cultural improvements and opportunities for students of color on campus; decades of mentoring students; and a history of philanthropy and service to his alma mater.

Joseph Patterson Jr. was honored in June 2019 with an Alumni Award.

A resident of Bloomfield, Conn., Patterson passed away after a battle with pancreatic cancer. He is survived by his wife, Mary Mattke ’71, two sons, David and Derek, and eight grandchildren. A visitation and celebration of life is set for Aug. 28 at The Lodge in Windsor, Conn. To carry on his legacy, the Joseph F. Patterson Jr. Scholarship at Lawrence University has been created.

Patterson was honored by Lawrence three years ago with a Gertrude Breithaupt Jupp Outstanding Service Award, presented when he returned to campus for his 50th-year celebration as part of Reunion 2019. The award honors a graduate who has provided outstanding service to Lawrence.

“Your commitment to your career has not dimmed your commitment to the greater good,” reads a proclamation presented to Patterson. “You have tirelessly promoted student diversity and created support programs to ensure the success and achievement of all students.”

Patterson played a key role in launching the LU Black Alumni Network (LUBAN) and has provided significant philanthropic support to Lawrence through the years.

“This is a big loss for Lawrence,” said Louis Butler ’73, the former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice who credits Patterson with helping him and other Black students navigate the complexities of student life at Lawrence in the late ’60s and early ’70s. “He’s going to be sorely missed by everyone who knew him as a leader.”

Patterson also was back at Lawrence in 2017, when the 1967 football team that posted a perfect 8-0 record was inducted into the Lawrence Intercollegiate Athletic Hall of Fame. It was the second induction for Patterson, who went in as an individual honoree in 1999.

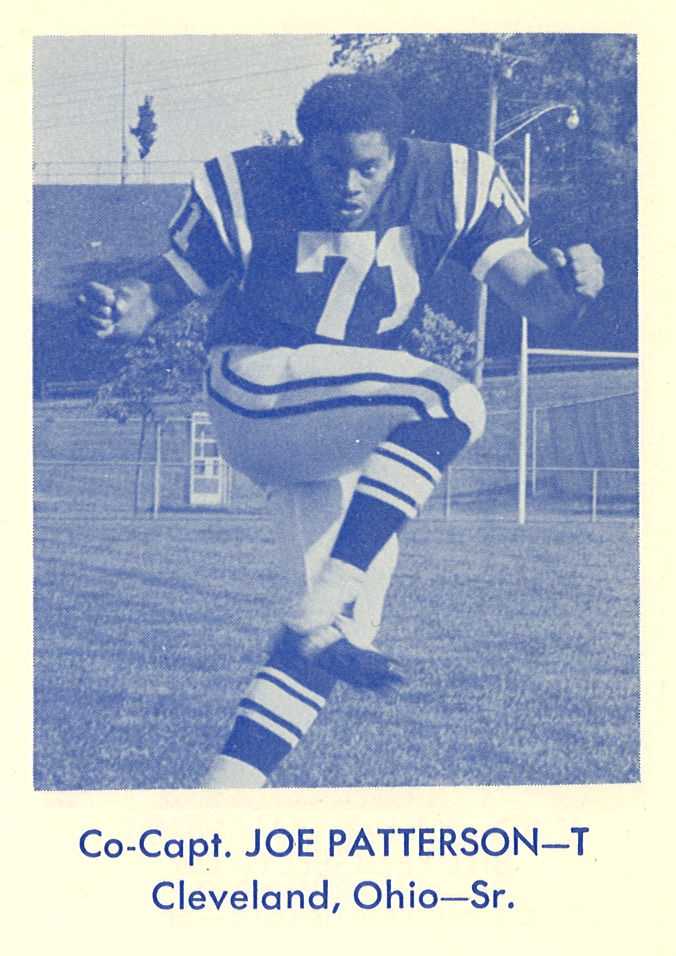

Joseph Patterson Jr., 1968

A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Patterson came to Lawrence and quickly became a mainstay on the Vikings’ offensive line for head coach Ron Roberts. He played on the defensive front as well. An All-American in 1968 and 1969, he was a three-time All-Midwest Conference selection.

Considered one of the greatest linemen ever at Lawrence, the 6-foot-4, 250-pound Patterson was a 13th-round draft pick in the 1970 National Football League draft, selected by Vince Lombardi, the legendary Green Bay Packers coach who had moved on to Washington. He is one of 12 former Vikings to have suited up for an NFL team.

Patterson would soon leave football behind, earning a master’s in business administration from the prestigious Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and launching a business career that would include leadership roles in global real estate and management of billion-dollar commercial property portfolios for Guardian Life.

He served as a member of the Board of Directors of the School of Visual Arts of NYC since 2000 and through the years has actively promoted and supported diversity of students on college campuses and in public high schools.

He never left Lawrence far behind, serving a term on the Board of Trustees and staying active in alumni circles.

A geology major at Lawrence, Patterson saw his impact grow both on and off the football field during his four years as a student in the late 1960s. Civil rights battles were being waged and only a handful of Black students were on campus. He emerged as a leader, advocating for change as he and classmates joined movements that were happening on campuses across the country.

He was the recipient of the university’s inaugural Martin Luther King Award, presented to a student who through scholarship, vision, and dedication mirrors the excellence for which Dr. King advocated.

He inspired those who were on campus at the time and students who followed, said Robert Currie ’74, who arrived shortly after Patterson graduated.

“Our tenure and our experiences were made somewhat easier by Joe,” he said. “Joe never checked out. He remained connected. He always found time to check in with the Black students who were there and asked questions that were very important about improving our experiences on campus.”

Richard King ’70 met Patterson after arriving at Lawrence as a transfer student. Patterson’s pull was immediate, a leader in every way, King said.

“We spent a lot of time in the dorms late at night talking about life and what was going on around the world,” he said.

The efforts of Patterson and his classmates led to the formation of the Association of African Americans, a student organization, and demands for change, including an increase in the number of students of color on campus.

“His passion really resonated with me,” Currie said.

On the football field, meanwhile, Patterson dominated the line of scrimmage, said teammate Clarence Rixter ’72, a running back.

“We were a great team, and Joe was sort of the anchor,” he said. “We were three yards and a cloud of dust. If you passed, it was a mistake. We ran the ball, ran the ball, and then ran the ball.”

Patterson, he said, was an undeniable leader on that team. He had no off switch.

“He always gave a speech that we had to cut short because the game was going to start,” Rixter said.

He called Patterson a fierce competitor whose dominance was widely respected by teammates and opponents. Rixter likes to tell the story of a practice drill in which he felt the wrath of an excited Patterson. He had made a move—"I gave him a leg and snatched it back and did the old Rixter spin"—that left Patterson grasping at air. And not at all pleased.

"Coach says, ‘OK, let’s run it again,’" Rixter said. "And I said, Coach, he knows where I’m going and there’s only one hole. So, I got the ball and Joe shredded the center and the guard, just a couple of chop blows and boom, they were down. And I thought, if you can’t step around him, you got to run over him. … Joe hit me so hard; it was the hardest hit I ever had in six years of organized football. All I could do was bite my mouth guard and pretend like it didn’t hurt. Then coach said, ‘Gentlemen, let’s run it one more time.’ I said, 'Nope. I'm done.'”

Patterson’s final interaction with Lawrence came this summer. He was scheduled to join Jerald Podair, the Robert S. French Professor of American Studies and professor of history, at Bjorklunden for a seminar titled African America in Slavery and Freedom. But Patterson had become too ill to travel. Instead, he recorded a video that talked of his own experiences with race in America, a journey filled with racism, pain, resilience, and strength.

“Joe had reason to be bitter, but he chose to be inspirational—that day and all the days of his life,” Podair said.