Caitlin White Magel ’09 isn’t surprised that Lawrence University is showing up on national rankings of schools whose science graduates have most consistently taken a STEM-to-Ph.D. path.

As she closes in on her doctorate at Oregon State University, Magel points to guidance during her sophomore year at Lawrence that set her on the road to being a marine scientist.

She came into Lawrence as an environmental studies major, and early interactions with her advisor, geosciences professor Marcia Bjornerud, further locked in her desire to study human impacts on natural ecosystems. But, she quickly learned, there were more options to consider.

“I was encouraged by other science faculty — and my scientist father — to consider the option of a double major in order to have disciplinary depth in a particular field while still being able to explore broader issues through the environmental studies classes,” Magel said. “By the end of my sophomore year, I declared a second major in biology.”

That led to participation in the LU Marine Program (LUMP), jump-starting what would become a deep interest in marine ecology and putting her on a path toward her Ph.D.

This is Lawrence - Excellence in STEM

Teaching STEM at Lawrence

She’s not alone in that experience. The number of Lawrence students earning degrees in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields on their way to successful completion of doctoral degrees places Lawrence in select company, according to a new report from the Council for Independent Colleges (CIC). In a national ranking that measures the percentage of a school’s STEM graduates from 2007 to 2016 who eventually earned a Ph.D., Lawrence comes in at No. 17, sandwiched between Harvard at 16 and Princeton at 18. It is a jump of 11 spots from the previous rankings, released in 2013. When the new rankings are broken down to women only, Lawrence comes in at No. 29. The CIC used National Center for Education statistics and National Science Foundation datasets that included public and private schools.

Those rankings aren’t by happenstance. They speak to the deep commitment Lawrence has made in the STEM fields, and the power that comes with small class sizes and the opportunity to do hands-on research in the sciences as an undergraduate in a smaller, liberal arts setting, said Stefan Debbert, associate professor of chemistry.

“The rankings are a sign that we are doing something right, that we are getting students invested enough in the sciences that they are considering future study,” he said. “But it’s also a challenge to us to make sure we’re sending them to graduate school well prepared. The goal isn’t just to get students to enter graduate school. The goal is, if that’s the correct choice for them, to have them in a position to succeed.”

Recent Nobel announcements hit close to home for Lawrence profs

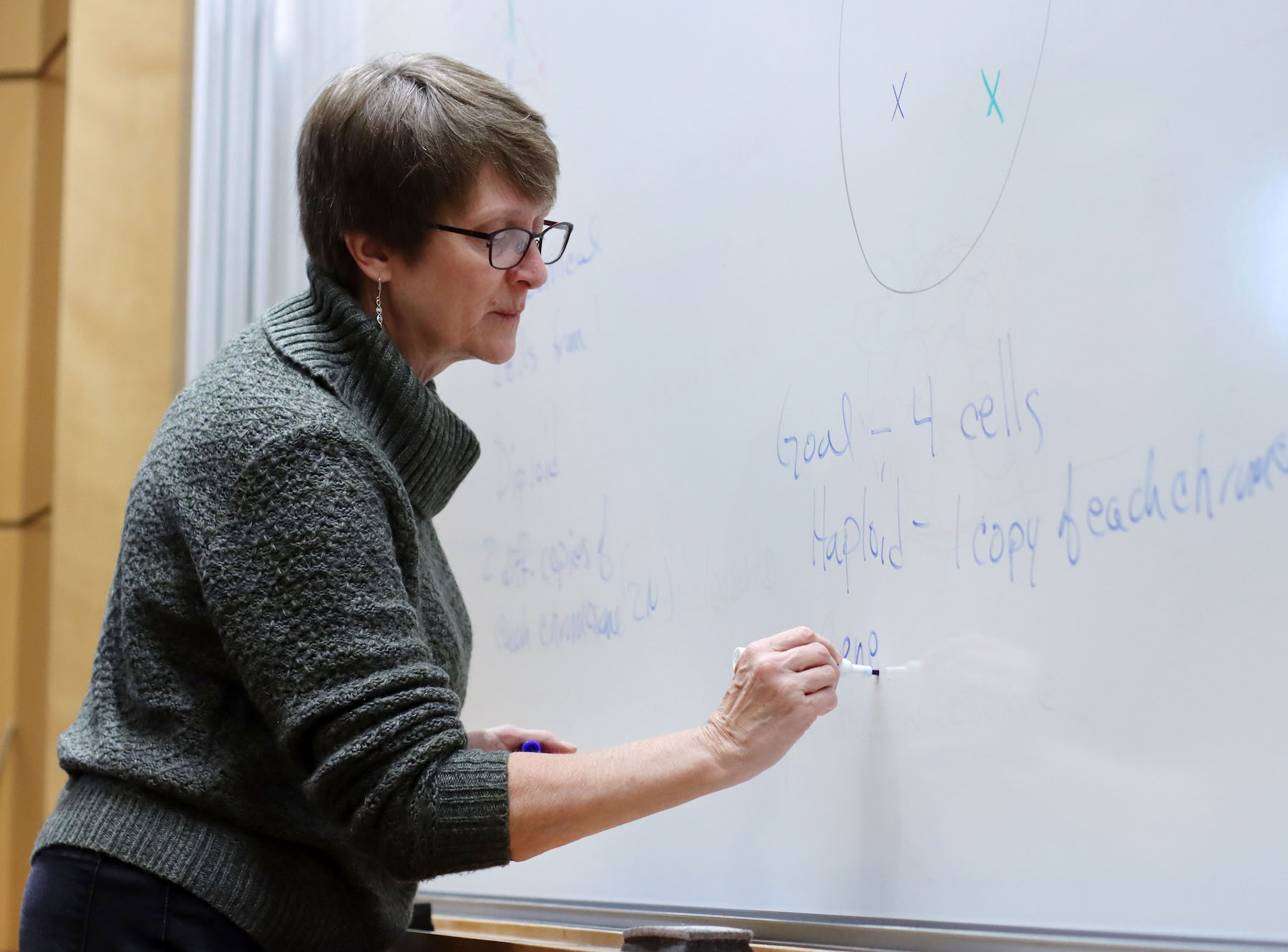

Elizabeth Ann De Stasio, the Raymond H. Herzog Professor of Science and professor of biology at Lawrence University, teaches Integrative Biology: Cells to Organisms.

A new approach

There is still much work to be done. Lawrence doesn’t show up on the CIC’s STEM-to-Ph.D. rankings when it measures African American or Latino graduates. The school’s numbers aren’t large enough to qualify.

That’s an issue that’s being addressed head on by Lawrence administrators and faculty across the sciences.

Debbert is leading an initiative to restructure how introductory-level science courses are taught. Lawrence was one of 33 schools selected last year to receive a $1 million grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) to implement its Inclusive Excellence Initiative via its Science Education Program. Another 24 schools were selected the year prior, part of HHMI’s push to reimagine science education to better engage students from all backgrounds.

Debbert is working with other science faculty at Lawrence to reshape how subjects are introduced and explored, how classrooms are structured, and how faculty interact with students. It puts more emphasis on the front-end science courses in hopes it’ll keep more students — and a greater diversity of students — in the sciences for the long haul.

“HHMI is motivated to help America fix its STEM pipeline problems,” Debbert said. “We have lots of students come into college thinking they want to major in the sciences, and we lose a lot of those students. HHMI is really pushing us to think about why we lose those students. Sometimes we lose them because we’re just not engaging with them enough. Students look around a giant science classroom and they think, ‘I don’t see people who look like me’ or ‘I don’t see myself as fitting in this environment.’ And then we lose them.”

Much of the HHMI work over the past year has involved training sessions with faculty and the redesigning of curriculum for introductory science courses, all with a focus on inclusive pedagogy. The revamped courses will be rolled out over the next two years.

There’s also a desire to retool a large lecture hall in Youngchild Hall to create a more modern science space, with the traditional tiered seating replaced with a dozen or so tables equipped with interactive technology. It would cater to the intro classes and serve as a launch point for science learning. Creating what Debbert calls a “science commons,” with a welcoming environment, is a big part of the new approach. Additional fundraising is being sought to make that happen, hopefully with construction beginning no later than summer, said Amy Kester, director of corporate, foundation, and sponsored research support. The goal is to have the room ready for the 2020-21 academic year.

Stefan Debbert on efforts to engage with science students early on: “We are working with them, getting to know what part of science motivates them.”

Building on success

The changes at the intro class level will build on the successes Lawrence has had elsewhere in the sciences. The “rallying cry,” Debbert said, is to get students excited about and engaged with science in those early classes so they stay with it long enough to see the possibilities that come with deeper, more specific study in the higher-level courses, be it in biology, chemistry, physics or related subjects.

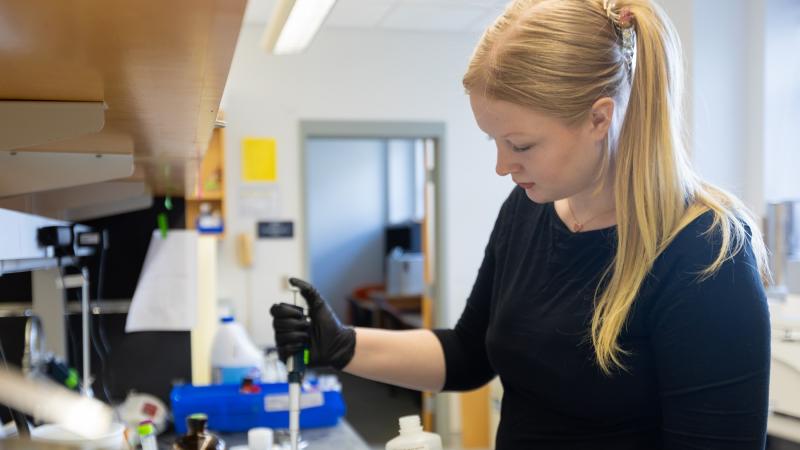

Part of that approach is giving students opportunities to do significant research, sometimes as early as freshman year. Students in the sciences at Lawrence are often doing research that students at other schools might not see until grad school.

“We have these students do research with us,” Debbert said. “So, they’re not just sitting in the back of a giant lecture hall falling asleep while someone talks at them. We are working with them, getting to know what part of science motivates them. We’re getting to know how they feel they can contribute, not just to their scientific field but to the world at large.

“I think that’s what drives a lot of our students to pursue graduate school. This idea that you really can have a massive impact in science.”

Lawrence, of course, has a much smaller enrollment than many of the public and private schools in the CIC rankings. Lawrence, with a student body of about 1,500, might graduate 10 to 12 chemistry majors, another 10 to 12 physics majors, and about 40 biology majors in a given year. Those smaller numbers, and the school’s 8-to-1 students to faculty ratio, help make the hands-on approach in the sciences possible.

That approach hooked Brianna Wilson ’21, a third-year biology major from Kenosha who wants to pursue a Ph.D. so she can eventually teach biology at the college level. An intro biology course during her freshman year opened her eyes to that possibility.

“The last five weeks of the term you design your own experiment with the professor,” Wilson said. “I was taken aback by that, that they’d throw us into a lab and let us design our own experiment. … I thought I wouldn’t be able to get a chance to do that until … I went to graduate school. That was pretty memorable.”

Path to a Ph.D.

Wilson is now envisioning a path not unlike that of Magel and other Lawrence grads working their way toward doctoral degrees.

For Magel, it was an opportunity to take part in LUMP that opened her to a new world. The Lawrence program provides a hands-on undergraduate experience in marine biology, including a two-week field study of a Caribbean island, the study of coral and fish biodiversity, and the exploration of reef ecosystems.

Caitlin White Magel ’09

“It was an incredible experience,” Magel said. “It was my first scientific experience in marine ecosystems, and also my first experience doing field-based research.”

Then, following her junior year, Magel garnered a summer internship with the NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates at Oregon State’s Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport, Oregon. That built on what she had taken from the LUMP experience.

After graduating from Lawrence, she would return to Newport for a two-year research assistant position with the EPA’s Pacific Coastal Ecology Branch, studying coastal salt marshes. That led her to her doctoral program focused on coastal marine ecology.

“Undoubtedly, the support and encouragement of many of my Lawrence professors, especially Marcia Bjornerud, Bart De Stasio, and Jodi Sedlock, helped put me on a path to success in graduate school,” Magel said.

That’s music to Debbert’s ears. The ongoing connection between student and faculty is a key selling point in a liberal arts education, the sciences included. That starts early at Lawrence and continues post-graduation.

“We really try to help students find out what it’s like to be a researcher,” Debbert said of the undergraduate work. “Being a scientist isn’t just sitting in a lecture hall and taking tests. Real science is about being curious and being OK with not knowing something and then going out and figuring it out. That’s what we really try to stress to our students.

“Yes, we’re going to teach the quantitative skills and the math and how to use the instruments, but we also want to make sure we’re teaching them how to communicate with each other, how to work with people who might not be very similar to you, how to come up with a research question, how to fail, and how to succeed after that.”

No one on the faculty is focusing on the STEM-to-Ph.D. rankings, Debbert said. The rankings are nice because they remind people that there is some serious science happening in the halls of liberal arts colleges, Lawrence included, but they don’t change a professor’s classroom approach or a student’s experience.

“Sometimes people seem surprised that you can have an actual honest-to-goodness real laboratory experience at a small school,” Debbert said. “If anything, these rankings show people that, yes, we do real science at Lawrence, and we care about it and we care about having our students learn how to be researchers, independent researchers.

“To us, that’s the main thing. It helps us communicate our story, and the story for liberal arts schools in general, which is, send us your scientists and we can help them grow in that way.”